The ship sailed beyond the sight of land, to a place where “there is no moral possibility of desertion, or application for justice.”

—James Stanfield, as qtd. by Rediker.

To board the slave ship was to abandon hope—unless one hoped for torture, degradation, and the destruction of human life in the name of commerce. Driven by profit motives, the wealthy of Europe engaged some of the most depraved men of their times to lead cruel voyages across the Atlantic Ocean. The center stage for this drama of human injustice was the slave ship, or slaver. Historian Marcus Rediker takes the reader on several hideous voyages across the Atlantic on these ships, telling the stories of the human lives that participated in the trade of captive Africans for money.

The Human Stories

Rediker primarily focuses on putting a human face on dehumanization. The Slave Ship covers 1700 to 1808, the period of the highest volume of slave trade by the British. Their sailors gave the journey from Africa to the Americas the name “the Middle Passage”. Subtitled “A Human History”, The Slave Ship examines the lives of key figures involved in the slave trade and the effects this unholy commerce wrought upon their lives. To call the trade horrifying hardly scratches the surface.

Rediker spares no gory detail in his recounting, save where the writers of the day could not even bring themselves to elaborate the torture and suffering that took place. Such was the case with James Field Stanfield, who witnessed what was “practised by the captain on an unfortunate female slave, of the age of eight or nine.” Field said of this event, “I cannot express it in words”, although it was “too atrocious and bloody to be passed over in silence” (Rediker, 152).

Rediker’s focus on human stories rather than facts and figures reminds us that the men perpetrating these crimes were not fantastic monsters but human beings. Men in Britain and the American colonies grew rich from the trade, men such as Humphry Morice and Henry Laurens. They were, after all, simply men, respected in their communities and occupying social positions of prestige and leadership.

The Slave Ship also recounts the lives of slaves such as Olaudah Equiano, who penned a tale of his experience aboard the slavers that contributed to the abolitionist movement with its tragic narrative, and men such as Job Ben Solomon. Solomon, a leader of his people, endured enslavement but was eventually recognized as a tribal leader by the British.

He returned to Africa not to liberate his people but to serve the interest of the Royal African Company, assisting the Europeans in putting even more Africans into slavery. Stories like this reveal the myth that the Atlantic slave trade simply consisted of European enslavement of Africans. Rediker tells of many African leaders and tribes who participated willingly, capturing peaceful people on their own continent to sell into slavery.

Rediker details the lives of John Newton and James Field Stanfield to paint portraits of the sailors on these terrible ships. Newton’s experience as a common sailor with a bad attitude eventually transformed him into an ardent abolitionist. Stanfield originally joined the slave trade to see the world and have adventures. He found despair, torture, and atrocity. He would write vivid narrative poetry that bolstered the abolitionist movement.

These were the fortunate ones, for Rediker tells many more tales of lives destroyed by the trade: free men reduced to slaves, families torn apart, tribes destroyed, healthy men crushed by disease and torture, and sailors reduced to empty shells after their voyages. By focusing on the human side of history, Rediker makes it come alive.

The Rise of Racism and Capitalism

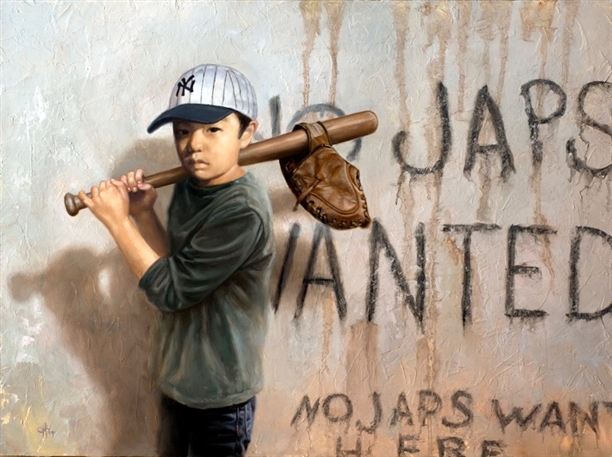

The Slave Ship touches many times upon the relation of the Atlantic slave trade to the rise of racism. Before the Atlantic slave trade, it was uncommon for people to see other people divided only by the color of their skin. Anyone—black, white, or brown—could become a slave in those days.

The Atlantic slave trade, however, grouped all Africans of many cultures into one single group: black. Rediker explores how far the division of black and white could be taken, where light-skinned people could be “black” based on their social status, and “white” became synonymous with “free” even for dark-skinned people. It often depended on which side of the barricade one ended up when revolt broke out on the ship.

Rediker also relates the Atlantic slave trade to the rise of capitalism. Slave ships brought manufactured goods from the Americas back to Europe on the return leg of their journeys, stimulating manufacturing in the colonies. Also tabulated for the reader are the facts and figures of production: millions of pounds per year of rum, tobacco, and cotton produced with slave labor and exported to Europe.

Rediker could have spent more time on the rise of the corporation. While he mentions companies such as the Royal African Company formed solely for the purpose of enslaving human beings, he does not explore the lingering social impact of forming companies to profit from human misery. To see the lasting effects of this form of commerce, observe companies like Raytheon who profit by creating bombs with no other purpose than the mutilation and destruction of human beings. The Atlantic slave trade and other European ventures into the Americas founded this policy of corporate cruelty.

Rediker often returns to his theme of the slave trade’s destruction of lives—not just the lives of slaves, but of all those involved. When Rediker describes the incredible atrocities committed by sailors against their captives, the reader might form an idea of privileged white people abusing blacks. Even more shocking, perhaps, is the examination of the lives of the sailors. In most cases, captains victimized sailors to nearly the same degree they abused the slaves.

In Rediker’s portrait of the slave trade, the lines between the victimizer and the victimized disappear. What emerges is a web of cruelty that enveloped everyone it touched. Rediker tells of many sailors who were swindled into the voyages by unscrupulous means: through falsified debts in bars, threats of imprisonment, and false promises from recruiters.

In some sense, the sailors were captives just as much as the slaves, and their lives were wrecked just as thoroughly. Rediker tells of sailors cheated out of wages, abandoned in ports, riddled with disease and injury, and left to scrape a mean existence on the docks as homeless, penniless human wreckage. While the mortality rate of slaves on the ships was high, about one in four sailors died on the voyages, too.

It appears the only people to benefit from the Atlantic slave trade were the richest, most powerful men living far removed from the ships, reaping most of the profits and enduring none of the hardships.

Two Criticisms

Rediker’s approach to telling stories results in a narrative that jumps around chronologically. His approach shows how individuals changed over time, but makes it difficult to envision the flow of historical change. From an educational perspective, a single timeline would make the big picture clear. The Slave Ship seems to be several books combined into one, making an overview almost necessary for a complete understanding.

Because each chapter stands on its own, the reader runs into much unnecessary duplication. By the halfway point, the reader has already encountered the same or similar descriptions several times: slaves jumping overboard, manacles “excoriating” flesh, dysentery smearing the hold with excrement, sailors being swindled into signing on to the ships, and the speculum oris.

Each time these horrors appear in The Slave Ship, they receive a treatment as if they appear for the first time. This causes the book to lose momentum as it progresses. While it starts with a bang, the last third of the book includes many redundant descriptions.

While manacles get many paragraphs, world events sometimes receive much less. In a study of the development of capitalism, one might expect a bit more time studying various wars, inventions, and other world-shaking events. The development of ship-building from a hand-me-down trade to a full-blown global science merits a page or two. The relation between science and the slave trade bears more exploration.

Abolition movements receive a similar treatment. While Rediker speaks of the contributions of Equiano and Stanfield to the abolition movement, he does not spend much time discussing the movement itself. This might be an important part of the puzzle he leaves out. How the abolitionists contributed to the British and American bans on the Atlantic slave trade would form the proper end to this book.

Conclusion

What can we learn from The Slave Ship? Nothing good, it seems—only that humans require no fantastic gods or monsters to inflict cruelty upon them. They will take care of that themselves.

History bears out this lesson. From instruments of medieval torture to the Spanish invasion of the Americas, from the Nazi concentration camps to Ku Klux Klan lynchings, the greatest danger to man continues to be man himself. When his greed for money and power drives man’s capacity for cruelty, we find no limits to the savagery he will inflict upon others.

The Europeans un-ironically viewed themselves as civilized and the Africans they tortured as barbarians. Despite the years that have passed since the Atlantic slave trade, that attitude remains prevalent in many countries and cultures around the world. One group dehumanizes another group, and the cycle continues.

Is the entire planet a slave ship driven by greed, fear, and hate? Is there no application for justice? Are we doomed to destroy other people in the pursuit of profit forever? The Slave Ship raises these questions and leaves them unanswered, while brutality in the name of commerce continues to destroy lives around the world in the twenty-first century.

Collector’s Guide: The Slave Ship: A Human History is available on Amazon in ebook or paperback or hardback. Marcus Rediker also wrote one my favorite books about Atlantic pirates and Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea about general conditions of life at sea in that era.

:focal(638x484:639x485)/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/87/df/87df4f91-10eb-417e-82d4-d585554a2f2c/02_babysquid_008.jpg)