Tags

black lives matter, black panther party, book review, david f walker, fred hampton, graphic novel, history, indie box, Indie Comics, Marcus Kwame Anderson, racism

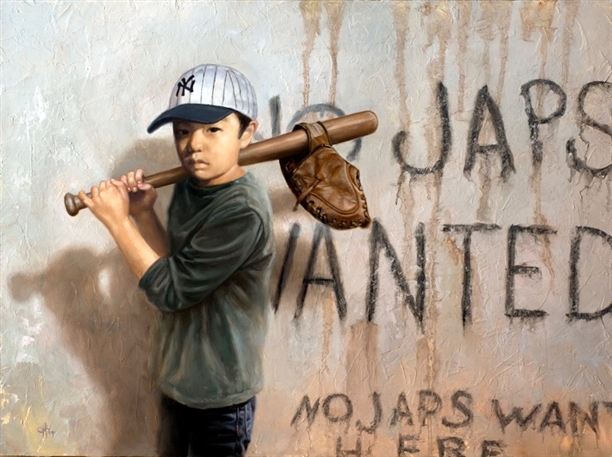

A simplistic understanding of history most likely associates the Black Panther Party with violence, as opposed to the nonviolent path advocated by activists such as Martin Luther King, Jr. and John Lewis. And it’s true that, like the more militant Malcolm X, the Panthers embraced the idea of arming themselves as a form of protection against the widespread lynchings and police attacks that claimed the lives of far too many black people in the twentieth century. The Panthers were, after all, originally called the Black Panther Party for Self Defense, and it’s easy to understand their disillusionment with nonviolence when acts of unspeakable brutality were constantly perpetrated against members of their communities.

This graphic novel reminds us that the Panthers also provided free breakfasts for thousands of impoverished schoolchildren over the years, and created schools that educated hundreds of black youth. Education has long been a key component of empowering marginalized members of societies, and learning is always easier on a full belly rather than in the throes of poverty-induced starvation. Perhaps that is why so many racist Republican-led state legislatures and governors are currently seeking to remove not only unsavory aspects of American history from our public schools and universities but also provisions to feed children raised in poverty. These are actions clearly designed to perpetuate oppression and create a permanent under-class, regardless of the political rhetoric that accompanies them.

As this graphic novel also illuminates, the leadership and ideologies within the Black Panther Party were not unilateral. They were tumultuous and splintered, with many Black Panthers seeking more peaceful solutions through political activism at the same time when more extremely violent factions broke off into radical groups such as the Black Liberation Army. And while many Panthers are rightly remembered as champions of equal rights and progress, some were either mentally unhinged, drug-addicted, or downright criminal. To use broad brush strokes to paint all Panthers in the same light is too simplistic and ignores the realities that eventually led to the Party’s end.

This book was not my first introduction to the Black Panthers, but I still learned a lot from it. It takes ample time to examine the multiple parties from which it arose, the role of women in the party from its admittedly sexist roots to the time when its leader was a woman, the massive and multiple infiltration campaigns by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI to discredit the party in the eyes of both blacks and whites, and the collusion between the FBI and local police forces that led to violent, unprovoked, and fatal assaults on the Panther’s leadership and membership.

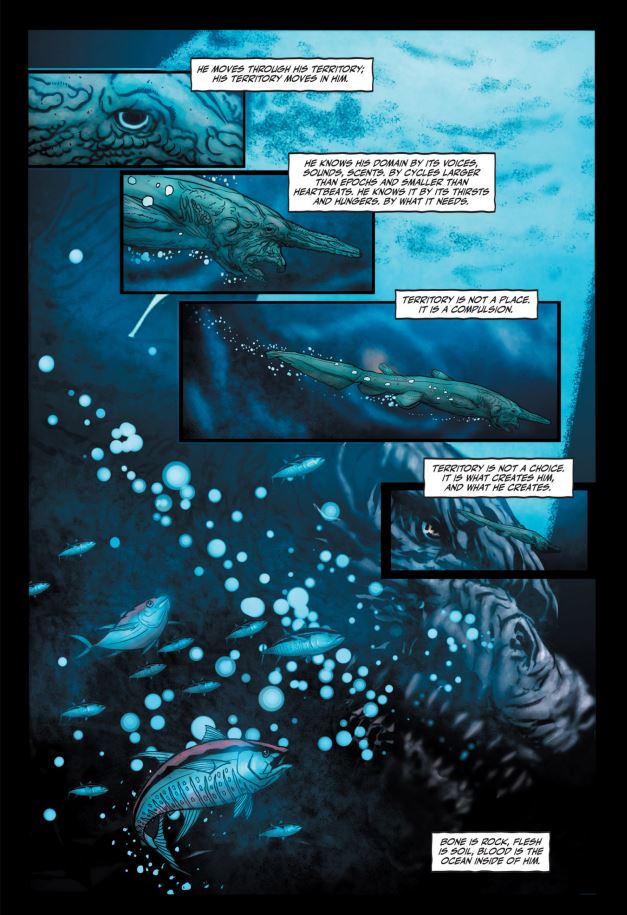

The book itself is more like an illustrated history than a graphic novel. Only a handful of scenes are given a comic-book treatment in terms of sequential images that incorporate story, dialogue, and captions. Most of it consists of illustrated exposition, including the historical profiles of many Panthers. So, if you are brave enough to pick up this book, be prepared for reading a lot of expositional history lessons.

Also understand that some of the violent encounters depicted here are almost too clean and bloodless. While I liked the artwork in general, there were moments where I felt that the horrors on the page lacked the visceral punch of witnessing the much more horrifying reality the Panthers endured.

That being said, you could watch the 2021 film Judas and the Black Messiah to get a grittier gut-punch feel for the FBI’s infiltration of the party in pursuit of its goal of murdering Fred Hampton. The film also has a great soundtrack of songs from the period and, much to my surprise, briefly depicts the revolutionary band of percussionists and spoken-word artists, the Last Poets.

Overall, this book makes a good companion to the graphic novels March and Run by John Lewis, since it features many of the same key players in the civil-rights movement while highlighting the spectrum of philosophies, the internal conflicts, and the successes and failures of both the movements and the individual players involved. It’s an important history for us to remember if we ever hope to correct the mistakes and injustices of the past and build a more equitable future.

Collector’s Guide: The Black Panther Party: A Graphic Novel History is available in paperback and digital editions.

:focal(638x484:639x485)/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/87/df/87df4f91-10eb-417e-82d4-d585554a2f2c/02_babysquid_008.jpg)