Vietnam is a comic book written by Julian Bond, published in 1967 after he was expelled from the Georgia House of Representatives for opposing the American war in Vietnam. T.G. Lewis illustrated.

Read the entire nineteen-page comic online (free) at the Sixties Project.

I found Julian Bond’s Vietnam while looking for a website about the Vietnam War. I needed to review a site for my final paper in History 273: American Involvement in Vietnam 1945-1975. Here is the final paper.

Preserving the Voice of Dissent:

The Sixties Project and Julian Bond’s Vietnam

“History is written by the victors.” — Winston Churchill

Churchill’s famous quote passed into common usage as “the winners write the history books.” Or, as Kwame Nkrumah, former President of Ghana put it, “The history of a nation is, unfortunately, too easily written as the history of its dominant class.” If this is true, then what happens to the voices of dissent in the aftermath of cultural clashes? Do their points of view simply vanish, swept away by the tides of history? Sadly, this once was the case. But today, internet technology provides a tool to preserve pieces of history that might otherwise be written out of the books. This technology becomes more cheaply produced and widely available every year. People of all beliefs and nationalities now take advantage of its potential for wide distribution at a low cost. The ease of use also increases rapidly as companies like WordPress take the coding and technical know-how out of building web sites. Online, the voices of dissent find a forum. Historians, however, face the challenge of preserving a legacy of pre-internet communications media in this new format. The Sixties Project embraces our need to preserve and distribute historical, pre-internet media via the web. We will examine how The Sixties Project succeeds or fails at this mission in presenting an otherwise forgotten comic book about the Vietnam War: Vietnam, by Julian Bond and T.G. Lewis.

The mission statement of The Sixties Project, based in Tucson, Arizona, declares,

“We believe that this cooperative use of technology can help us efficiently and broadly disseminate information about the Sixties. Such dissemination ensures the preservation of information which might otherwise be lost. We intend a resource concerning the Sixties that will encourage immediate end-user access to the broadest possible range of audience — scholars, librarians, teachers, researchers, and students.”

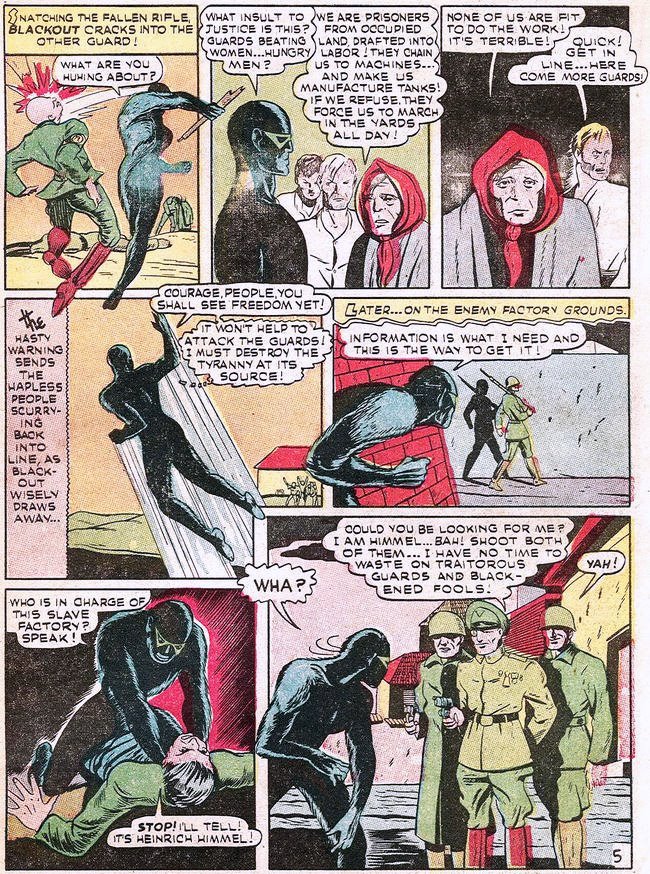

The online media exhibits include buttons, a collection of political protest posters, and a comic book entitled, simply, Vietnam. This comic book, in a basic layout of four panels per page, calls into question not only US policy on Vietnam but also the means of carrying out that policy. In a few short pages, Bond lays bare the cultural differences and perspective of the Vietnamese people, the massive ‘underground’ domestic opposition to the war, and the racial inequities inherent in the armed forces. Bond also makes it clear that black soldiers were sent to die in a misguided war by a nation that forced them to use separate toilets back home, a remnant of Jim Crow laws that seems unthinkable some generations later. The black and white line work by artist T.G. Lewis achieves what every comic book artist wishes to achieve: a seamless union of form and content. The pictures support the ideas and enhance them, visually driving home the ideological points. In a perfect comic book, one does not get the whole effect from either just the words or pictures. Instead, the full impact arises from the symbiotic relationship of the two taken together at once. The Sixties Project preserves the integrity of the original pages, and therefore the artist’s original intent when shaping them. Vietnam is easy to navigate through its nineteen pages, the scans are legible and clear enough, and even the most unskilled internet user can access it freely. The images load quickly to create a nearly seamless user experience.

The readability and accessibility of Vietnam make it a success in an era where publishers and artists still struggle to make a satisfactory online experience of the comic book medium. Scott McCloud’s vision of the evolution from print into a digital comic era has yet to fulfill its promise. Everyone from industry giant Marvel Comics to independents like Marc Hansen has digitized their comics, but fans still prefer the print medium. Like the migration of books to Kindles, iPads, and laptops, the medium transfer leaves something to be desired. Books have a tactile quality and substance lacking in digital reproductions, and were already interactive centuries ago. Many collectors enjoy the feel of the paper in their hands and the smell of time-worn pages. In a culture with glowing screens in every room, purse, and pocket, books provide a way to unplug, whether to stimulate one’s mind or simply to escape into fantasy. Digitization requires the glowing screen, and therefore cuts off that quiet time of the mind provided by books. What the internet does very successfully, though, is not replace the print medium but enhance the consumer experience of it. On thousands of personal websites across the globe, readers share their favorite scenes, their thoughts about various artists, and their love for the medium. A reader looking for new books has much more information at her fingertips than in 1967. Before the world wide web, one relied on a handful of hip friends to find out about new titles or perhaps older, obscure titles to enjoy. Today, that network of hip friends spans the globe. In any case, the major impact of the digital age on comic books is that many out of print works can be shared with hundreds or thousands of people who cannot find or afford print copies of these titles. Thus, the internet preserves the past so that the present and the future may discover it, enjoy it, share it, and learn from it. Vietnam, for example, cannot be found at major online retailers or auction markets at the time of this writing. If not for the Sixties Project, this important work could have ended up swept under the proverbial rug.

From a historical perspective, Vietnam is that most rare production among comic books: a clearly antiwar statement. Comic books have a long history as tools to further pro-war interests in America. World War II brought American comics, in their infancy, to a major onslaught of pro-war propaganda in Golden Age titles like Captain Battle, The Invaders, Captain America, Daredevil Vs. Hitler — just to name a few. Comic books joined other media forms — posters, newspapers, radio — in unilaterally promoting US war policy. Vietnam stands out from this herd in a decidedly antiwar position, yet it can hardly be found anywhere but a single web site. We hear its voice of dissent fading into faint echoes, with only the internet to sustain its message.

The Sixties Project briefly notes that Julian Bond authored this comic book in 1967 after “he was expelled from the Georgia House of Representatives for opposing the American war in Vietnam.” It may not be necessary to know Bond’s history to appreciate this work, but this small blurb barely scratches the surface of Bond’s significance. In fact, one could hardly undertake a study of black history in twentieth century America without touching on the life of Julian Bond. He attended, at Morehouse College, the only class ever taught by Martin Luther King, Jr. He founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, leading anti-segregation protests in Georgia. In the ill-fated Democratic Convention of 1968, Bond received a nomination for Vice Presidential candidacy. Though the first black American to receive such a nomination from a major political party, the young Bond at age twenty-eight could not qualify for a job with a minimum age requirement of thirty-five! However, he went on to serve as the Chairman of the NAACP from 1998 to 2010 and authored or founded an extensive list of magazines and forums for black Americans. Clearly his political career was not abruptly terminated circa 1967 as The Sixties Project might erroneously lead one to believe. In fact, the Supreme Court found that the Georgia House of Representatives had violated Bond’s freedom of speech and had to re-seat him. He went on to serve four terms in the House and six terms in the Georgia Senate, helping found the Georgia Legislative Black Caucus along the way. Vietnam was no one-off project by a man who lost his government job. It was, rather, one of many works in a lifetime of civil rights activism, and not the first or last time Bond would vocally oppose the war. Understanding Bond’s civil rights history puts Vietnam in a greater historical context than The Sixties Project indicates.

Julian Bond wanted to send a message. Did he succeed? While Vietnam succeeds formally as an online comic book, it also succeeds in raising questions: questions about racial inequities in the States, cultural misunderstandings of the Vietnamese by the US, and the inefficacy of the foreign policy decisions around the war. In 1994’s Vietnam: An American Ordeal, George Donelson Moss covered all of these topics extensively. But to the average reader, his book may seem dense, dry, and difficult. Bond’s Vietnam, however, conveys most of the sociological questions Moss raises, and it does so in nineteen pages. Total reading time? About fifteen minutes. This speaks of the power of the comic book medium, its ability to use words and pictures to communicate complex, challenging ideas in a succinctly comprehensible fashion. While many people think of the comic book as purely the territory of jokes and super-heroes, Vietnam does not dress up war in a pair of colorful tights and entertaining fist fights. It uses the medium not as a fantasy outlet but as a work of education, sociology, and a philosophy of social responsibility. In 1967, this was an exception to the rule, and it continues to be the exception today. For comic books that question cultural norms and political ideologies, one must usually go to smaller presses like Last Gasp. But even these exceptions are decades old, with limited print runs and low distribution. Last Gasp’s Anarchy Comics from 1978 presented populist uprisings in four- to ten-page stories. Images and text render revolutionary lives more comprehensively than a stack of textbooks. Meaning becomes clear in moments, not hours. Forbidden Knowledge, also from Last Gasp in 1978, unflinchingly portrays the horrors visited upon Japanese civilians by the atom bomb. It draws a stark contrast to the flag-waving “might makes right” attitude of Golden Age publications like Atoman, in which the atom is our friend, and where we did a good thing nuking “the Japs.” Perhaps only Robert Kanigher’s Sgt. Rock stories for DC came anywhere near questioning the very concept of war itself at a major publisher. We owe a debt to The Sixties Project for preserving Julian Bond’s Vietnam, because far too many books like it make it to the shelves today.

Despite its cogent presentation and social relevance, Vietnam suffers from a lack of citation. When Bond tells readers that twenty percent of the South Vietnamese forces deserted, or that the number of blacks killed in combat zones was disproportionate to the numbers of blacks enlisted, do we to take that at face value alone? If the original book had a citations or a recommended reading page, it is not reproduced here. The Sixties Project makes no attempt to verify Bond’s claims. While subsequent studies seem to back up Bond’s arguments, failure to cite sources only hampers historical research and calls into question any social critique. Furthermore, readers will find nothing at The Sixties Project about the context and impact of this comic book. How and where was it distributed? How was it received? While we can find information about Julian Bond as a historical figure, what other works of art has T.G. Lewis produced? Searching for the artist yields a confusing mass of potential matches for his name. When readers want to drill down and find out more about Lewis, Bond, and this book, they are on their own. Also, the website suffers from a lack of attention, its last update going back to 1999. One might hope that the intervening twelve years have produced many more potential exhibits for The Sixties Project, or expanded their research. The final drawback: resolution, or lack of it. Surely Lewis’ artwork and lettering was much tighter and crisper in its original state. The visually impaired may find the captions inscrutable and they do not magnify well at greater zoom levels. Overall, the image quality remains adequate as a historical exhibit, but one would hope someone with a decent scanner gets a hold of the original artwork before it disappears.

Some of these drawbacks stem the source material itself, Vietnam, and some from the adaptation to the internet. But despite these limitations, The Sixties Project still provides an enlightening and educational web site that preserves a history of dissent for future generations. Readers can overcome many of its limitations by taking the initiative to do further research. And, if this website stimulates additional research, then it has achieved its mission. It may not be an exhaustive biography of Julian Bond, but it can inspire the reader to learn more about him. Its accessibility and ease of use reward the adventurous reader who finds the site. Rather than criticize its limitations, one might instead be overjoyed that they took the time to accomplish what they did. Subsequent historians like George Donelson Moss only reinforce and reiterate Julian Bond’s criticisms of the Vietnam War in 1967. Vietnam stands as a lucid, eloquent testimony against the dominant ideology. Clearly not everyone from that time believed we could bomb the Vietnamese people into freedom. If the winners do indeed write the history books, then perhaps we must rely on the dissenters to write the comic books, and upon the internet to preserve their voices.

Sources

Di Caprio, George et al. Forbidden Knowledge #2. “Atomic Follies.” Berkeley: Last Gasp, 1978.

Howard, Matthew. “Atoman: Getting Nuked is… Awesome?!” Online post. 4 Jul. 2011.

MarsWillSendNoMore.com

https://marswillsendnomore.wordpress.com/2011/07/04/atoman-getting-nuked-is-awesome/

Kinney, Jay et al. Anarchy Comics #2. Berkeley: Last Gasp, 1978.

McCloud, Scott. Reinventing Comics: How Imagination and Technology Are Revolutionizing an Art Form . Harper, 2000.

. Harper, 2000.

Moss, George Donaldson. Vietnam: An American Ordeal (6th Edition) . New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1994.

. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1994.

The Sixties Project. Vietnam: An Antiwar Comic Book. 28 Jan. 1999. Online exhibit. 7 Jul. 2011.

http://www2.iath.virginia.edu/sixties/HTML_docs/Exhibits/Bond/Bond.html

The graphics herein made available by The Sixties Project are copyright 1991 by the Author or by Viet Nam Generation, Inc., all rights reserved. This text may be used, printed, and archived in accordance with the Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright law. This text may not be archived, printed, or redistributed in any form for a fee, without the consent of the copyright holder. This notice must accompany any redistribution of the text. The Sixties Project, sponsored by Viet Nam Generation Inc. and the Institute of Advanced Technology in the Humanities at the University of Virginia at Charlottesville, is a collective of humanities scholars working together on the Internet to use electronic resources to provide routes of collaboration and make available primary and secondary sources for researchers, students, teachers, writers and librarians interested in the 1960s.